|

| Oil sketch on canvas, 8" x 10", 2013, Amanda Clyne |

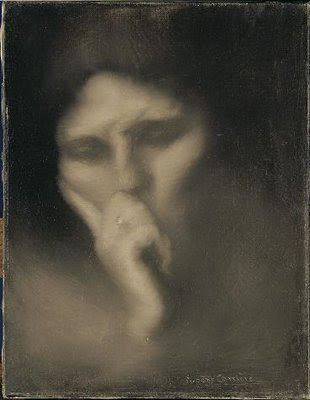

I must confess. I constantly feel the desire to slip inside another's skin. I am fascinated by the prospect of entering the internal worlds of others, and I have pursued art for its special capacity to create this experience. Although I have not always been an artist, I have always been an avid viewer of the arts, experiencing genuine and intense personal connections to artworks that seem to magically mirror my own private sensibilities. At its best, the experience feels as if I have met a kindred spirit, sharing such a deep reciprocal bond that loneliness becomes impossible. Now as an artist, I have begun to think of the act of making art itself as an empathic exercise, and wonder how the notion of empathy may serve as a paradigm for my art practice.

The concept of empathy has been engaging the interests of those in philosophy, psychology and neuroscience, and while there is no standard definition used by researchers, there are three critical elements that seem to be agreed upon:

• The Other: The experience of empathy begins with the desire to understand the mental or emotional state of another. The focus is not on the self but on the other.

• Imagination: Empathy involves the act of imagining as the means to overcome the challenge of perceiving what another person is experiencing in a particular circumstance. This notion of imaginative simulation has its roots in the 18th century with the moral philosophizing of Adam Smith:

"By the imagination we place ourselves in his situation, we conceive ourselves enduring all the same torments, we enter as it were into his body, and become in some measure the same person with him, and thence form some idea of his sensations, and even feel something, which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them." (1)• Shared Response: The purpose of this imaginative undertaking is not merely to understand another person's experience, but to share in that person's response. Graham McFee declares empathy to be "an achievement", the result of an active form of engagement:

"...empathy is, in this way, relational in a stronger sense than, say, even sympathy. My sympathy with you (or for you) does not require that you feel anything: but at the centre of the idea of empathy is precisely a sharing of some psychological state or condition. So both your contribution and mine are required." (2)Each of these elements seems to lie at the heart of not only viewing art but making it. It's easiest to see this in the work of artists such as Gillian Wearing or Bill Viola, where the work is made through interacting with real people -- recruited subjects in Wearing's work and hired actors in Viola's work -- and where empathy is in some way the stated subject matter of the work itself.

But for those of us dealing with images or abstract forms, can empathy still be considered a defining aspect of our approach? I like to think that it can. I feel it at each stage of my painting process. From the very beginning, there is always something "other" that needs to be imaginatively embodied, whether a person, an image, a form or an idea. And once paint hits the canvas, the materials themselves demand an empathic treatment. Any attempt to control or dominate them are inevitably rejected as futile. They seem to respond best when they are collaborators in the process, nurturing, expanding and supplementing my own decisions and sensibilities. As an image comes to form on the canvas, it too takes on a life of its own. In the midst of composing a work, I always have the sensation that the image looking back at me has an inherent form that must be discovered in dialogue with the painting itself. It is not all about me. Empathy for "others" must guide me throughout.

I find purpose in imagining empathy as the paradigm of my art practice. As a viewer, I have no doubt that empathy is an intrinsic part of art's transformational power. Now as an artist, I am finding it to be no less of a critical force in art's creation, helping to generate an empathic network that ultimately joins together the source/subject, artist, artwork, and viewer.