part three: thinking

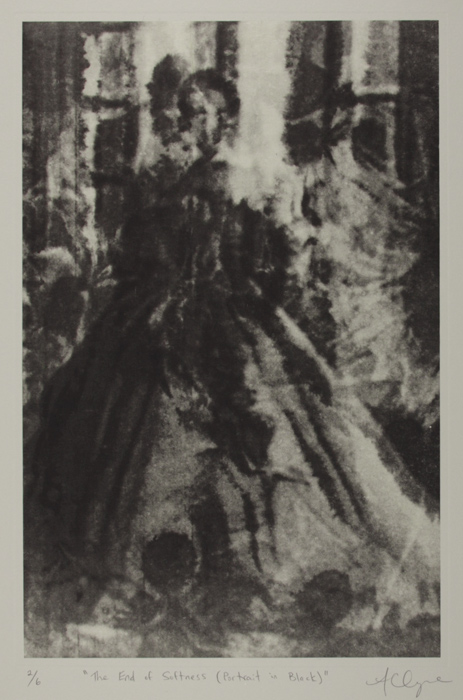

Inspired by portraiture, couture and the history of painting, I always look to images where artifice reigns – in historical and contemporary portraits of the elite, where women are enveloped in an excess of ornament and the expression, pose or surroundings suggest a potent mix of both power and vulnerability.

portraits of portraits

““There is no equivalent in portraiture of a one-way mirror: the process demands mutual exposure.”

Daniel Marcus”

Trying to negotiate the gap between the seen and unseen, I consciously avoid making portraits of individuals whom I know personally. To interrogate the visual, I want to examine the assumptions and clues that are generated by physical appearance alone, extracted from extraneous knowledge garnered from more intimate sources. While I prefer to avoid the specter of biography and self-portraiture, I admit that I may use the faces of strangers as surrogates for my own.

Amanda Clyne, "Tarnished", oil on canvas, 2010

““I always appropriate, so that I can never fully be myself, but have boundaries to constrain my exploded self.”

— Glenn Brown”

Portraiture is a strange pursuit. An artist asks a model to pose, to pretend to freeze a moment in time, and in turn, the model grants permission to become the subject of intense scrutiny and study, as if to confess that their own visuality is somehow an inadequate representation that requires a deeper imagining. How do I know what I look like if I cannot see through your eyes? How do I know what you see unless you show me? Perhaps you see more than I think, or perhaps you see someone who is not me at all.

In the studio, I make portraits of portraits. Instead of a sitter posing for me, I look at photographed images, examining the web of relationships among image-makers – model, artist, and me.

In the images I choose, models concoct creatures of fiction, posing to satiate the needs of the myriad eyes upon them, both real and imagined. In the historical painted portraits of royalty and nobility, women comport themselves with formality and restraint, servicing the demands of their social position. The historical royal portrait was, in the words of Javier Portús, a “highly codified straitjacket”* intended to legitimize and propagandize the power class, not to expose emotional intimacies. Set within a sea of luxurious ornamentation, the woman’s face is almost a forgotten afterthought. It is not a portrait of a woman, it is a portrait of an image.

In contemporary fashion photographs, the model is similarly recruited to represent a world of ambition and aspiration divorced from any personal reflection. Her extravagant state of adornment is the spectacle to behold. In her excessive visuality, the woman becomes invisible. She is all image.

* Javier Portús, “The Varied Fortunes of the Portrait in Spain,” in The Spanish Portrait: From El Greco to Picasso, ed. Javier Portùs (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2004), 54.

the spectacle of femininity

““...men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. [...] The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object — and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

— John Berger”

I am often asked why I only work with images of women. The simple answer is that my work is fundamentally rooted in my experience of the world, which occurs unavoidably through my sense and presence of being a woman. By representing my perceptions through images of women who exist far from common experience, I know I am subjecting my images to the baggage such images carry, but I am drawn to these women’s particular position as spectacle. Women generally carry the greatest burden of visuality, to which men are only beginning to succumb. It is women who bear the longest history of being seen as little more than surface.

Amanda Clyne, "Excavating Artifice, Study", oil on canvas, 2014

““Images have an invincible power, and power, in its turn, manifests itself through images; it feeds off of images. Power always maintains its distance, imposing a solemn detachment from the real: it is ready to strike, but always from a hidden refuge. [...] Power therefore stands behind the scenes. ... Reflected in hundreds of images, power still tries to flee its representation, it won’t be caught: it disperses itself, opposing any analysis. The problem, therefore, is not how to destroy an image: the problem is how to reach power, how to represent what is hiding behind images.”

— Massimiliano Gioni”

Spectacle is always related to power. It is an expression of dominance and vanity. It is a command for authority and attention. It is a tacit admission that real power has been denied.

If spectacle is wedded to power, beauty is its handmaiden. Through spectacles of beauty, power is asserted, claimed, demonstrated or demanded. But beauty also portends vulnerability, and in the images of women that fascinate me most, power resonates but vulnerability lurks within. Draped in impractical gowns that flaunt wealth and privilege, a woman stands contained, staring at the spectator with a dignified yet fragile composure. Wealth offers up a cloak of invincibility, as if nothing that looked so perfect could ever be flawed, lost or suffering. In the heart of such beauty, darker truths may reside.

In Francis Bacon’s screaming Pope, he flays Velasquez’ original portrait of pomp and power. The destruction of the image is an unleashing, the Pope’s power shred into a torrent of repressed rage and violence. There is no beauty in Bacon’s world. In contrast, I am drawn to the quandaries of the beautiful and the more melancholy states of yearning and loss, but I sympathize with Bacon’s method of finding intensity in restraint. In the worlds of beauty that seduce me, I seek to strip away the artifice from images that propagandize power and glorify the mode of display in order to expose a more human, quiet desire for empathic connections, a desire so intense and fragile it can verge on a kind of madness.

““...as if to say “This is what it feels like to have a body,” and also, “This is what it feels like to be a painting.”

— Daniel Marcus ”

Amanda Clyne, "Excavating Artifice, I", oil on canvas, 2014

the strategy of repetition

““Without objectivity you’re left with doubt, and doubt insists on plurality.”

— Christopher Wool”

I never make just one. For each portrayal, I try and try again. Through processes of dissolution, extraction and erasure, I work to disinter the image’s inner-workings. Whether I am deleting pixels in Photoshop, scarring a copper etching plate, forcing a printer’s ink to bleed from a fresh print, or obliterating thick strokes of paint from a stained canvas, I dissect an image until I have distilled my findings into a new work. And then I do it again. And again. I keep reworking the original in multiple iterations, shifting approaches, moving between media to find new ways of getting beneath the surface. I return to the same image over and over, repeating and renewing my efforts to strip it of its artifice.

““Experiences recalled are generally more satisfying and enlightening than the original experience.”

— Agnes Martin”

A mode of repetition can imply reproduction or redundancy, merely a mimicking of the original that can never spark the magic or intensity of the first encounter. But to repeat can also be to take the opportunity to linger and to look again, to experience the encounter not as if it were the first time, but rather knowing that the first time could not possibly have been enough to discover all that there must be. To repeat is to follow one’s perpetual desire for more, and to be cognizant that with every look, something is missed. The original is merely the tease, a beckoning call to return. There is always more. Regarding the words of Agnes Martin quoted above, Briony Fer writes:

“Recollection is somehow more vivid, or put another way, original experience is a pale reflection of its repetitions. Repetition is understood as a means not of deadening but heightening experience...” *

As I return to the original image again and again, fresh eyes make new discoveries, new discoveries breed new images, and the cycle of desire is renewed.

* Fer, “Drawing Drawing,” 191.

the fragment's allure

In my pursuit to unconceal an image, I search for its source of vulnerability. In the process, I am forced to methodically destroy it. The resulting remnants and ruins form the basis of my own re-imaginings. I dismantle the original spectacle and prompt its gradual metamorphosis through a re-building from fragments -- fragments of time, of images, of perspectives and processes, of ideas and sensations. Ultimately, each work is itself a fragment, an offering to the viewer to re-imagine what has been torn away.

““Real wholes are ephemeral and start falling apart even before they are finished. Their fragments last much longer and yet they too are subject to decay and corruption. The only thing that is truly immortal is the lost whole that we reconstruct on the basis of fragments, that never existed in reality, and that therefore can never perish.”

— Glenn Most ”

As a representation and reminder of the ephemerality of that which is now out of reach, the fragment always implies a loss. It is the visible remnant of a fugitive whole. In Glenn Most’s analysis of fragments, he proposes that the fragment’s evocative power lies not in its reference to the lost whole, but in the imagined whole that is created by the viewer in response to the fragment’s presence: “…the hypothetical whole we can imagine on its basis can come to seem far more deeply satisfying to us, because we ourselves have helped to create it…”[36]. By virtue of this imagined whole, the past becomes the present, as we imaginatively inhabit the implicit body that strives to be seen.

postlude

For all this talk of an erotics of looking and making, one might imagine my work to be visually indulgent in response. And yet my final works convey a surface and image that are barely there. However, they reflect my experience of the erotic which recalls the nature of the “great spirit” Eros, as described in Plato’s The Symposium. Like an artist, Eros is born from the union of Resource and Poverty:

“…he schemes to get hold of beautiful and good things. He’s brave, impetuous and intense; a formidable hunter, always weaving tricks, he desires knowledge and is resourceful in getting it; a lifelong lover of wisdom; clever at using magic, drugs and sophistry.” (Plato, The Symposium, trans. Christopher Gill (New York: Penguin Books, 1999) 39-40.)

But despite his resourcefulness, curiosity and passion, as the son of Poverty, he remains in a perpetual state of need.

“Sometimes on a single day he shoots into life, when he’s successful, and then dies, and then (taking after his father) comes back to life again. The resources he obtains keep on draining away, so that Eros is neither wholly without resources nor rich. (Plato, The Symposium, 40.)

In the studio, I wage the same battle. In search of an adequate representation of my sensations, I am never satisfied when an image begins to find resolution. For me, a lack of resolution forms the more honest picture.

We are all image-makers, whether in paint, pixels or persona, and every image contains a vulnerability and resistance to exposure. Every image inevitably represents the lack of all that remains invisible and unreachable.

““[He] is both strengthened and harried by a small persistent voice deep inside him that repeats, “I want I want I want.” There is something terrible about these protagonists who are so consumed with desire.”

— Lee Siegel”

I am addicted to the quiet, intense, contemplative act of looking and the imaginative and collaborative act of making. I see desire and vulnerability in every surface. To speak of surface is to envision the physical world as a series of fragile layers, where every exterior cloaks an implicit interior of meaning and sensation. Everything I see and everything I make is a construction of layers. Everything is a veiled body waiting for observant and sensitive eyes to see past its artifice.

Amanda Clyne, Wallflower #6, oil on canvas, 2017